Note: This story is not to scare anyone from traveling, including to Zimbabwe. The country is beautiful, and aside from one or two bad apples, the people I met were welcoming and kind. The main lesson to take away from this is that even the most seasoned of travelers can find themselves in a not-so-favorable situation, and that we must always be extra cautious in how we present ourselves in places of conflict.

I woke up in a daze. It was my last day in Botswana and we were headed to Zimbabwe, one of the last stops of my three week African road-trip.

But a stomach bug had been going around our group, and despite feeling I have an invincible immune system, it got me the night before. I spent the majority of the night tossing and turning with my head in a toilet. I was weak and dizzy. As I was ensuring my room was packed up for our 8am departure time, I realized I forgot to fill out my Zimbabwe immigration form. I quickly scribbled my info down, with my passport number memorized, hardly using a second thought to write down key details.

“Occupation: Journalist.”

I’m a freelancer: a blogger, a content creator, a journalist, an occasional bartender. I never really know what to write on my immigration forms for my occupation, but out of my many hats, journalist (or “writer”) is the most globally recognized term. While I’m aware that there are negative connotations with the “J” word in certain countries and regions of the worlds, I did not think Zimbabwe was one of them. I knew so many journalists, content creators, and other media folks who had been to Zimbabwe, no one ever mentioning an issue, posting pictures of themselves near majestic Victoria falls or on safari.

I didn’t think twice.

I drank some electrolyte powder in an attempt to feel human again, and off we went.

We got to the border, and because I wasn’t feeling too hot, I wanted to get in line first so I could swiftly return back to the car to sit down. I approached immigration and handed over my form, along with the $45 cash required for double entry into Zimbabwe since I planned to do a day trip to Zambia the following day.

“You need to fill in your home address,” he quickly barked. Of course I missed a box; I was rushing, I thought

“You’re a journalist?” he asked, as he paused with a look of shock, emphasized by an overarching lifted eyebrow.

“Yes,” I said, “But I’m just here for holiday.”

“I need you to fill out some extra forms,” he said without looking up at me. “Step to the side.” I watched him put my passport to the side, behind the thick shielded window, as he moved on to the next tourist.

An internal alarm was raised, and I knew immediately that writing journalist was not the wisest move for Zimbabwe, despite the reasons being unclear, but I waited patiently, stayed calm, and stepped to the side as I had been asked to do. I watched other people from my tour group get swiftly stamped through, passports back in hand.

After a few minutes, my guide came over to ask why I was waiting. “All good?” he said.

“Oh, they need me to fill out extra forms because I’m a journalist.”

He immediately swooped me away, wrapping his arm around me tightly and dragged me far from the immigration line toward the parking lot.

“You didn’t write you’re a journalist, did you?” He asked.

“Yes… I did … why? Was I not supposed to?” This is the moment the panic began to sink in.

“No, no, no, no,” he said. His panic made me more panicked. My guide is from Zimbabwe, born and raised, and knows the laws a lot better than I do, so seeing him spiral did not provide me with the utmost sense of comfort, and I knew instantly I was in deep shit.

“Am I going to get arrested?” I said repeatedly. All of those episodes of Locked Up Abroad, CNN reports of journalists being held for espionage, my friend who went to Iran with a drone and was held for five hours for interrogation, all came crashing into my sick, dehydrated body, the adrenaline reviving me ever so slightly.

He couldn’t answer if I was going to get arrested, and just kept saying, “Let me talk to them.” At one point, he mentioned that American journalists are almost always synonymous with being a spy, something I knew, and yet wrote it down anyway. In that moment, I would have done anything to take back writing what I wrote.

I wanted to believe there was absolutely no way I could be arrested in Zimbabwe for the simple stroke of my purple ball point pen, one singular word on an immigration form, but I knew it didn’t matter. Whatever picture they wanted to paint from my critical error was already in the works, and I was left in the waiting room to hear my fate.

As other people from my group came toward me smiling with their passports in hand, excited to be stamped in a new country, they had no idea the horrors going through my mind. I told a few in low whispers, “I might get arrested for writing I’m a journalist.” Some with the mandatory, “you should’ve never written that” (yes, loud and clear), others saying they’d pool together a fund to bribe the immigration officer.

All I could do was wait.

I couldn’t tell you how much time passed, or what time this was even happening at; the clock froze. My guess is it had to be around 9 or 10am, based on what time we left the hotel.

The thoughts going through my mind quickly switched from erratic to calm, calm to erratic. “I cannot make this phone call to my mom,” was a consistent one, along with accepting my fate, wondering what I was going to eat in Zimbabwean prison. A surprising thought was I immediately felt duped by traveling. I came to Zimbabwe specifically to see Victoria Falls. Was a waterfall worth my freedom? In a strange way, my visit felt like a scam.

Finally, my guide came back. “You’re okay, but play it cool, you need to sign a paper,” he said, looking more stressed than I was. “He’s very upset.”

Hearing those magic words, “You’re okay,” was only slightly a relief, but I tried to strategically think of what I had in my corner to prove I’m not a spy. For starters, I was wearing an orange frilly dress, red lipstick, and a zebra scarf. I thought, well I certainly don’t look like a spy, but I wasn’t sure how much that mattered. Secondly, I was with a group of tourists in a tour group, making me also being a tourist even more obvious. Thirdly, if I had any redeeming chance to explain myself, I’m a food critic and travel writer, writing about hotels and restaurants in NYC, which I had plenty of proof of; not geopolitics in Africa or even in the USA.

So, I approached the immigration officer with a smile on my face, and acted cool as a cucumber.

“Hi,” I said in an annoyingly peppy voice.

“Okay, I need you to sign this. When do you leave Zimbabwe?” he asked, this time his tone a little lighter, but still no eye contact to be had.

“Well I’m supposed to go to Zambia tomorrow—“

“Yeah, that’s fine, you can go to Zambia and come back in. But when do you leave to depart the country?”

“I fly out of Victoria Falls this Friday,” I said, as my words left my mouth, they landed on the page as he wrote down “vic falls airport.”

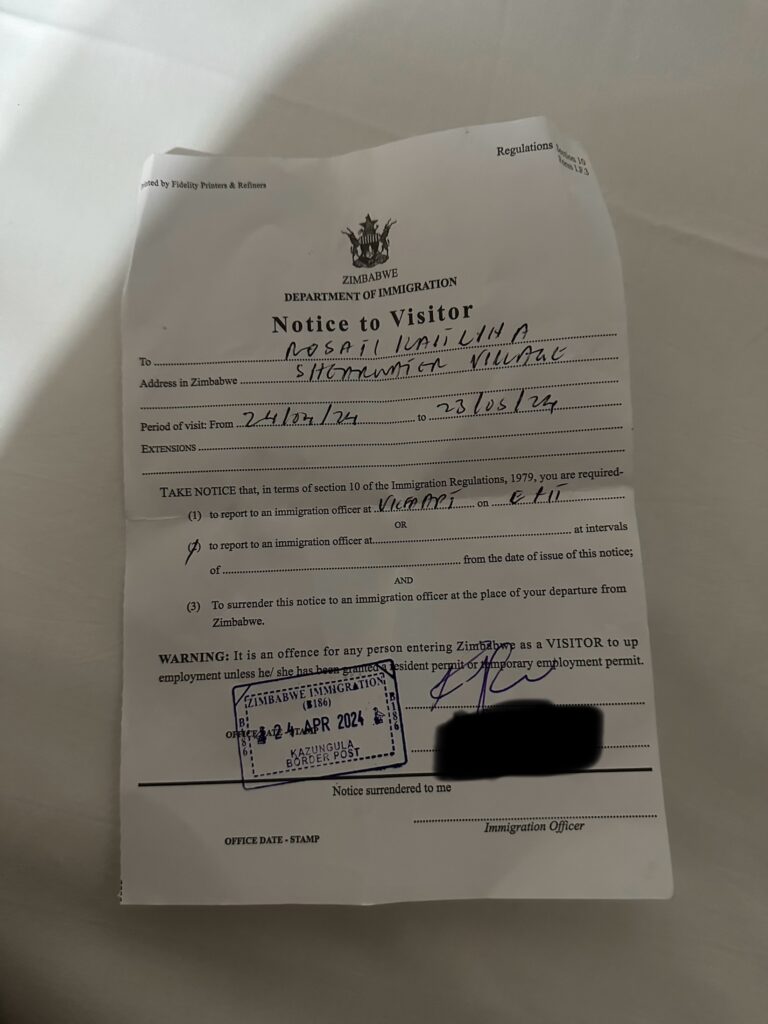

He handed me the paper to sign. It was fairly generic and simply stated I wouldn’t work in the country. I signed.

“Next time, write you’re a mechanic,” he said. I wasn’t sure if I was supposed to laugh, but I did.

I was then instructed to walk back toward the group, still no passport.

Finally, my guide came back toward us, with a stack of passports in his hands (a few other folks were waiting on their passports due to a confusion with visas, not for being spies).

As the only American in the group, I spotted mine immediately. My guide showed me the paper inside and said, “He said you need to turn this in at vic falls airport, and you need to keep it on you at all times incase the police or military personnel wants to see it.”

I didn’t respond, grabbed my passport, shoved it into my fanny pack, and ran into the car. Get me away from this border.

_______

Now that I was in the country, the elephant in the room was, how on earth was I supposed to have a “good time” in Zimbabwe, and suffer through the anxiety over the next two days knowing my fate of turning in this paper? Turning that paper in would bring attention to my situation, would raise questions, and my gut instinct said, “Fuck the paper; play dumb.” But I didn’t know if there was a bounty on my back, that I was now in some system and I was being watched. I had to give my phone number at immigration, and I questioned if spyware had been implemented on my phone, a real thing done to journalists all over the world, which I am familiar with from my background in cyber law.

Our group had immediate plans to go get lunch over the gorge of Victoria Falls, and then spend the day at the waterfalls. There was nothing I could do, so I did my best to enjoy myself. We sat down for lunch, and I thought, “What if this was my last meal of freedom?” and promptly ordered a passion fruit mojito.

I took in the power of Victoria Falls, and when I could get my guide alone, I asked him. “Was I really going to get arrested?” He told me they were, at the very least, going to bring me in for questioning, but he talked them out of it and gave them money to buy a drink. This raised a red flag for me and wondered if the whole thing was just an act of corruption, a common occurrence at African overland borders. That was, at the very least, my best case scenario. But I knew I wanted to call the US Embassy to be absolutely sure. At this point, I still didn’t quite grasp the relations between the US and Zimbabwe. My guide also told me to be very careful, to not take photos of anyone in uniform, to not talk about what happened openly in the country because “you never know who’s listening,” and that there was a chance they’d want to look through my photos at the airport when I left.

As soon as I got to my hotel room, I hid in the bathroom, crouched in the corner, and called a trusted friend, who is also a journalist. I wasn’t sure if calling the embassy was a smart move, or would create a paper trail of guilt for something I did not do. He validated my concerns, but also asked to get my parents’ contact information, just incase no one heard from me after Friday, the day of my flight. I did not want to accept this fate; I did not want to give him my mom and dad’s cell phone numbers. I did not want those calls to ever have to happen.

By the time I made the decision that calling the embassy was a wise move, they were closed for the day. Their hours let me know they opened at 7:30am the following morning, so I would call at 7:30 sharp. My other genius plan was to change my flight from Zimbabwe to being out of Zambia instead. I had plans to head there the next day regardless; the borders between the two countries are extremely lax, and this would allow me to ignore that paper completely. But, I wanted the advice from the Embassy prior to making this decision (a decision that would cost me close to $4,000, which I frankly, didn’t really have).

I looked through my search history and my text messages and deleted anything that could be used against me. The strategy was to be over paranoid. Complained about something related to the trip? Delete. Mentioned any recent published stories? Delete. The one that really got me was, when I was looking through my search history, I was trying to determine if I could retrieve USD from a Zimbabwe ATM. Fake USD are a huge problem in Zimbabwe, but after a plummeting economy, USD is the official currency of the country. I had googled “Can you fake USD out of an ATM in Zimbabwe,” about a week prior, but the word “fake” was meant to be “take” — I had just been typing too fast. I deleted it immediately.

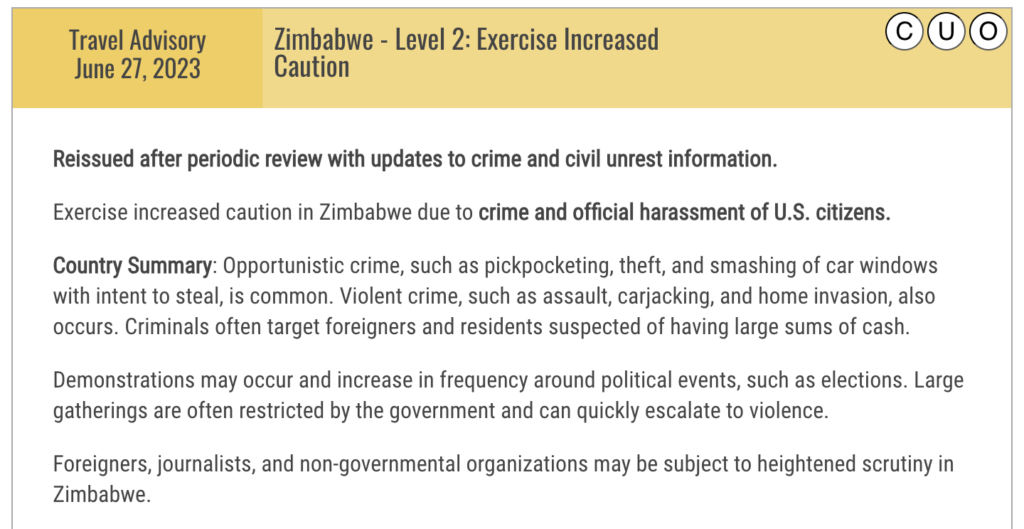

I used my VPN to go into deep research about US and Zimbabwe’s relations. Prior to traveling, I had seen the US travel advisory and nothing stood out to me (and I often find those advisories to be quite alarmist). Upon a closer look, I saw that it specifically said, “Journalists may be subject to heightened scrutiny.” I also learned that the US, in late March 2024 (I traveled in April 2024), had imposed sanctions on Zimbabwe, making their relations worst than ever.

_______

I woke up early the next morning and called the US Embassy in Zimbabwe emergency line. “Press 2 if you’re an American abroad in an emergency.” Did this constitute as an emergency? In my brain, it certainly did. “2.”

A man answered the phone, and I explained the situation while, once again, whispering, crouched in the bathroom. When I was done explaining that I said I’m a journalist, he kind of just said, “Yeah,” and didn’t sound too surprised. I further explained that I write about restaurants in NYC, hotels, and solo female travel.

“I’m going to Zambia in, like, an hour. Should I just stay over there and change my flight home from there?” I said.

“You could. But if you choose to stick with the original plan, the worst thing, most likely, you’re going to face is some additional questioning. The biggest risk is that you’ll miss your flight if it takes a while,” he said.

“So, I know you can’t really answer this, but am I going to get arrested?” I asked.

“It’s a valid question,” he said. “It would not fit a pattern; it hasn’t happened since 2008, and there’s not an election going on right now, so it would not fit a pattern.”

And finally, the golden question. “Do I have to turn that paper in?”

“If you were given clear instruction to turn the paper in, yes, you. need to turn the paper in.” I hated this answer.

After speaking with him, I felt a little better, but naturally, still not great. I decided to stick with the original flight. I went to Zambia for the day, and getting stamped back into Zimbabwe somewhat felt like a death sentence, but I convinced myself to stick with the story, the true story. I’m a food journalist. I prepped by taking screenshots of all of my recent published work, all of which were solely based around restaurants in New York City since I had been traveling.

_____

I went to the airport the next day and got there four hours early. I was ready to get this shit over with.

I approached immigration, and the thud of my heartbeat was so loud that I was sure everyone around me could hear it. My best valley girl voice was put on; act like an idiot. I handed over my passport, and then the paper, saying as nonchalantly as I could, “I think I’m supposed to give you this paper?”

The immigration officer took a moment to look at it. I was prepared to be interrogated based solely on what the US Embassy had told me. He looked, and did not look up, and finally said, “What do you do for an occupation?”

“I’m a food writer,” I said, now knowing to not use the big bad “J” word.

“What?” he said.

“A travel and food writer,” I said. “I think they just wanted to make sure I was here for holiday; but yeah, I’m just here to take selfies with the elephants and waterfalls,” I said, laughing.

He laughed, too, and stamped me out. That stamp was the sweetest sound I ever heard.

I headed to the lounge, and didn’t feel I was in the clear until I was in the sky. But a few hours later, off I went. And I now write this to you from the comfort of my childhood bed in Upstate New York.

_______

What’s the lesson here? For one, don’t write journalist on your immigration form. But beyond that, I got too comfortable, maybe even too confident, in my travels. I often don’t think twice when I write down my occupation; journalist and writer, in my world, are interchangeable, the same way journalist and spy are interchangeable for particular immigration officers and countries. There are other careers that can raise a red flag, too. One that comes to mind is “lawyer.”

I think the feeling of being duped into headed to Zimbabwe was valid. I felt tricked; I know so many people have been to Victoria Falls, and my only image of Zimbabwe was a pretty set of gushing water with rainbows over it. There’s danger in visiting a destination without fully understanding it. I didn’t take the proper time to do my research before heading there, because I just assumed it was safe, the same way I assume everywhere is safe because I think media often portrays negative narratives of certain countries, particularly those in the Middle East and Africa.

This is where I failed. It is good to create your own perspective, but it is also good to be aware.

I went to Zimbabwe unaware.

That travel advisory that explicitly states journalists are heightened to scrutiny has been up since June 2023, almost a year after I entered the country. Had I just taken the time to read it more thoroughly, I would have never ended up in my situation.

Even with all of that being said, while I likely will personally never go back to Zimbabwe out of fear that I’m somehow in a system somewhere, I don’t write this to discourage you, or anyone, from traveling there. I just encourage you to learn from my very critical errors, and proceed to Zimbabwe, or anywhere else in the world, with a hair more caution than I did.

Really glad everything worked out.